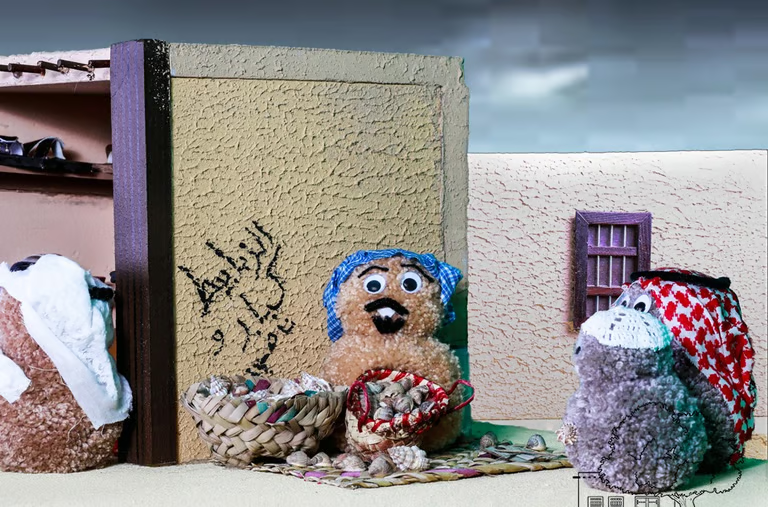

Al-Shawi was one of the traditional Kuwaiti professions, namely sheep herding. The shepherd gathered the sheep brought to him by the families of the neighborhood (Fereej). Each neighborhood had its own shepherd who collected the sheep in the morning, preparing to leave the neighborhoods for outside the city wall of Kuwait. After collecting sheep from each household, the shepherd relied on his donkey to carry his needs inside a “Kharj,” a sack made of burlap used to store food and sometimes to carry newborn goats. Shawi Athbiya was considered one of the most famous shepherds in the Jabla district. Another well-known figure was Shawi Al-Mutabba, who was famous for a chant he sang to children upon his arrival:

Kiya Shawina — Shawi Al-Mutabba

Calling his mother — bringing him dates

Ice was rare and precious, and obtaining ice blocks was difficult, as priority was given to cafés, fishermen, and ice shops. In alleys near homes and places where passersby gathered, the seller placed ice blocks wrapped in burlap to prevent melting. Ice was sold by weight, and each buyer carried a small flask to store the ice and keep it from melting.

Al-Naddaf, also known as Al-Mudarrib or Al-Qattan, was the craftsman responsible for cleaning and sorting cotton or wool to make mattresses, covers, and quilts. Before cotton, he used sheep wool to stuff cushions or mattresses (Dawashiq). The Naddaf transformed compressed cotton full of impurities into clean, soft cotton like silk, using a bow to clean and refine it. Demand for the Naddaf increased during Eid and weddings, to prepare new mattresses and cushions for guests. He began by stripping cotton from its old covers, spreading it on mats under the sun to ease cleaning and loosening. The process involved a wooden rod (Al-Mudarrab) striking a thick string stretched on the tool (Al-Tanja), producing a soft sound that some found soothing. The cotton returned to its natural white color, then the Naddaf placed it into new covers, sewing them by hand with cotton threads.

Al-Saffar was a profession specialized in maintaining and cleaning copper tools after they oxidized or turned black. Among the most important products of the coppersmith were: cooking pots, large plates, coffee pots, strainers, sieves, and copper bowls.

This was a well-known profession among women. The seller prepared and sold Bajella (fava beans) and Nakhi (chickpeas), cooked and served in small plates with black pepper sprinkled on top. The seller usually sat in the neighborhood squares selling to passersby.

The phrase “Jleeb Ankhem” consists of two words: “Jleeb,” meaning well, and “Ankhem,” meaning to sweep or clean. Together, it meant cleaning the well of dirt and impurities. This profession was carried out by two men, often one of them blind. They roamed the streets calling out loudly “Jleeb Ankhem – Jleeb Ankhem,” carrying their tools: a rope, a bucket, and sometimes a ladder. If a household had a well or water reservoir that needed cleaning—especially if an animal had fallen in and died—the cleaners were called. Stagnant water with dead creatures was considered impure and unusable, so cleaning was essential. The blind man descended into the well, while his partner stayed above. The blind man’s descent was preferred so he would not be frightened by insects or creatures inside. He cleaned the well and removed the water using the bucket, then emerged to collect his wage before moving on to seek other work.

Al-Nakkas was the person who walked through neighborhoods calling out “Nakkas… Nakkas” to repair the millstone (Rahaa). The millstone consisted of two stone pieces, the upper one with a hole to place wheat grains, rotated by a wooden handle fixed on top. It was used to grind wheat (Jareesh) in the past. When the millstone became smooth from frequent use and could no longer grind properly, the housewife handed it to the Nakkas. He roughened and repaired the stone using tools carried in his bag: hammers, chisels, fine picks, and small tools. He reshaped the stone by chiseling and striking it to create teeth that made it effective again for grinding.

Al-Kandar meant “Qandouri,” referring to fresh water. The name originated from the Kanara language. “Kanar” means the sidr tree, and “Dar” means stick, shortened to Kandari. The Kandari used a flexible crescent-shaped stick with two pointed ends, from which two tin containers (similar to date or kerosene tins) were hung. The Kandari placed the stick across his shoulders, with the containers dangling from both sides, carrying water to households. This profession was a source of livelihood for many families in Kuwait.

Al-Sammak was the person who sold fish. The first fish market in Kuwait was established thanks to the Sammak family (Hajj Hussein Al-Sammak). The fish market was located near the vegetable market (Al-Furda). Fish sellers maintained strong relations with suppliers, fishermen, and wholesale traders known as “Jazafeen.” The fish market was roofed with palm trunks and mats, and in front of each shop there was a “Dajja” or wooden table used to display fish.

The vegetable market sellers, known as “Al-Tarrarih,” were vendors of vegetables and farm products. The singular form “Al-Tarraah” referred to the individual seller. They sold produce from Kuwaiti farms such as spinach, purslane, beans, dill, tomatoes, cucumbers, fruits like yellow melon, watermelon, nabq (jujube), and bambar fruit.

With emphasis on the letter “L,” Al-‘Imarah was a shop selling supplies needed by seafarers (wood, ropes, nails, etc.) and everything related to ships (such as the Boom). The last of these shops was Al-‘Imarah of Abdul Latif Al-Humr, which was restored by the National Council for Culture, Arts, and Letters.

Al-Halwaji was the craftsman specialized in making traditional Kuwaiti sweets. He used flour, sugar, cardamom, yeast, saffron, rose water, blossom water, sesame, and date molasses. Among the most famous sweets were: Zalabiya, Sab Al-Qafsha, Ghuraiba, Jawame’, Dandurma, Luqaimat, Zalabiya, Rahash, Halwa, and Simsimiyya.

Al-Bazzaaz was the seller of cloth and garments. In the past, he walked through neighborhoods, sometimes on foot and sometimes riding his donkey, calling out his goods. Women would come out to buy fabrics of their choice. Later, this profession evolved into shops and stores.

The herbalist, locally called Al-Hawaj or Al-Attar, was the person who sold special types of wild plants, grains, dried fruits, and fruit peels such as pomegranate and orange. These were mainly used in preparing medicines, in addition to other products like spices, seeds, and materials used in dyes. The herbalist was usually an expert in mixing herbs and remedies, some of which were imported from India, Iran, Yemen, Saudi Arabia, and the Kuwaiti desert. Among the items sold were thyme, basil, borage, ginger, dried lime, anise, henna, cardamom pods, and sidr leaves. Herbalists did not have a dedicated market but were spread across all markets in Kuwait.

The barber profession was very old and evolved over time. In the past, the barber was called “Al-Muzayyin.” He spent his entire day practicing his craft. Haircuts were mandatory, especially for children, who had their heads shaved weekly. The price was half a rupee for children and one rupee for adults. Often, the barber shaved the entire head, leaving the customer bald, though some requested specific styles. His tools included a razor (Mous), a small bowl (Tasa), a razor sharpener, cloth pieces, and soap for washing the head before shaving. Barbers also shaved or trimmed beards. Some barbers acted as folk healers, treating certain ailments due to their skill with the razor.

Al-Kharraz was the craftsman specialized in leatherwork. This traditional profession is still practiced today. The leather craftsman skillfully transformed hides into useful items for daily life. He produced sandals, water containers (Qirbah), milk bags (Saqa), oil flasks, rifle covers, and belts. His tools included carefully selected hides from tanneries, a large needle with a wooden handle, thick colored threads for decoration, a mallet for striking leather, a wooden wedge (Samba), a rough stone for smoothing, and scissors and knives. This profession combined utility with artistry, making leather goods both practical and decorative.

The “Zaboot” is a type of marine shell, conical in shape, containing a small mollusk that was extracted using a palm frond thorn. A proverb says “Zaboot Al-Naqaa” referring to anything small in size. These shells were boiled in pots and sold cooked. Sellers in the streets and near the fish market called out “Big and tender Zababeet!” They also sold “Huwaita,” a small ribbed shell with a tiny animal inside, also cooked and eaten.

Before the establishment of the Department of Education and the spread of government schools in Kuwait, there were private schools that taught the Qur’an, Islamic studies, and basics of reading, writing, calligraphy, and arithmetic. These were supervised by a person called Al-Mulla or Al-Mutawwa, assisted when needed by other teachers. The school was usually a small old house owned or rented cheaply by the Mulla, furnished with simple items like mats, straw rugs, a clay water jar, wooden boards for writing, and the Mulla’s chair. Parents brought their children to these schools and negotiated fees: some paid a monthly salary called “Mashahra,” while others agreed on a lump sum called “Qutooa,” paid after completing the Qur’an.

Some Bedouin women carried baskets of vegetables on their heads, such as greens and Ruwaid, grown by their husbands in farms. They sold these vegetables to the residents living near Kuwait’s city wall.